EXCLUSIVE: Looking Beyond Summer Box Office as Trends Emerge

September 4, 2013

With Labor Day the traditional end of summer, pundits survey the uneven landscape of a fickle summer. Disappointing openings and steep weekend-to-weekend drop-offs jarred execs and provided fodder for commentary and soul-searching. It may be easy to find irony in the titles of two financially successful movies — the low-budget “The Purge” and “This Is The End,” which spoofed the end of the world against a backdrop of contemporary Hollywood — to suggest that this summer truly marks the end for movies. But that would only happen if there were a total failure to recognize emerging trends, acknowledge this is not the first time Hollywood has faced a changing market and apply new ideas to shape the future.

Those first weeks of this summer did produce an unusual number of misses on the expected blockbuster “tentpoles” and smaller than expected hits. However, with Labor Day now behind us, Box Office Mojo reports overall box office this summer is up by 10.2 percent with a 6.6 percent increase in attendance and about $265.8 million ahead of last summer. Even “World War Z,” its challenging production chronicled and questioned by media in advance and the subject of a Hollywood and Swine humor piece headlined “Survival Odds Low for Paramount Execs After Collapse of Poorly Constructed Tentpole,” opened well with more than $66 million at the U.S. box office and has grossed $562 million worldwide with more than 62 percent of its take from international screens.

Those first weeks of this summer did produce an unusual number of misses on the expected blockbuster “tentpoles” and smaller than expected hits. However, with Labor Day now behind us, Box Office Mojo reports overall box office this summer is up by 10.2 percent with a 6.6 percent increase in attendance and about $265.8 million ahead of last summer. Even “World War Z,” its challenging production chronicled and questioned by media in advance and the subject of a Hollywood and Swine humor piece headlined “Survival Odds Low for Paramount Execs After Collapse of Poorly Constructed Tentpole,” opened well with more than $66 million at the U.S. box office and has grossed $562 million worldwide with more than 62 percent of its take from international screens.

The term “tentpole” as a word to characterize a bigger budget, blockbuster movie release first appeared in 1987, according to the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Frank Mancuso, then the chairman of Paramount Pictures, is said to have been the first to use the description when he explained to The New York Times film industry correspondent Aljean Harmetz his studio’s strategy of making several big-budget movies every year “that because of content, star value or story line have immediate want-to-see and are strong enough to support your entire schedule.”

Mancuso was talking about “Beverly Hills Cop 2” in a tale of studio fortune and misfortune in that summer of 1987 when “Ishtar,” with two of the biggest stars of the day and a budget to match, established its place as one of the most spectacular flameouts of all time.

Twenty-six years later, the hit song from “Beverly Hills Cop” — “The Heat Is On” — can describe some of the pressure the industry is experiencing.

Heat is energy, and can be a catalyst and not a cataclysm.

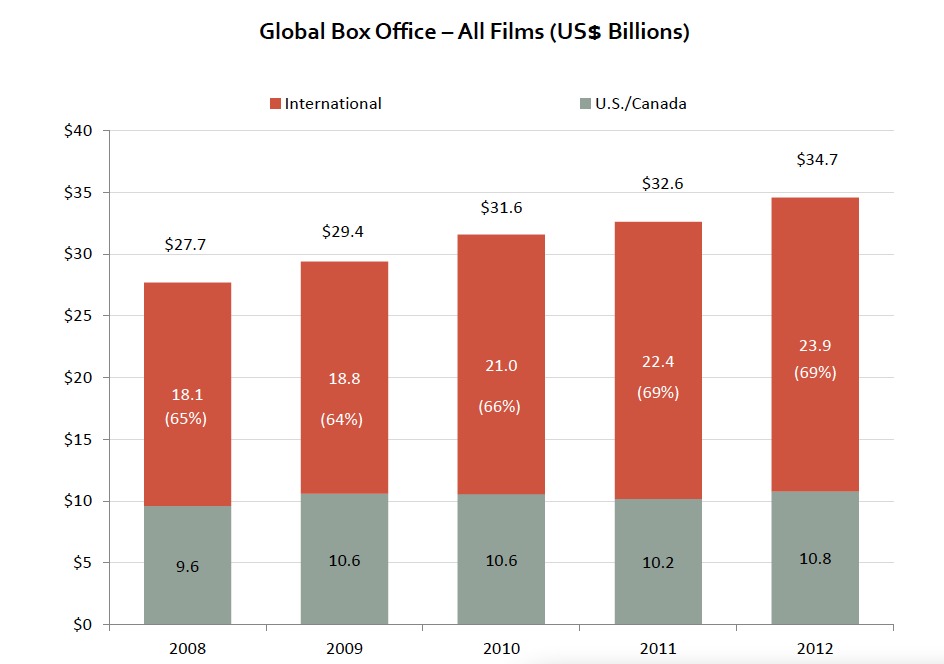

Back in 1987 another thing was just beginning to emerge: the rise of international box office. Today, largely through a great expansion of digital cinema, the opening of new screens around the world and worldwide day & date openings, revenues rise overseas as a counterbalance to the flatter results in the U.S. and Canada. All of the effort put forth by participants in the Digital Cinema Initiative and the predictions made by the ETC more than a decade ago demonstrate their vision and value today.

Source: Motion Picture Association 2012 Theatrical Statistics

Were it not for the premium paid for 3D admissions, box office in the U.S. has been at best flat and, adjusted for inflation, slightly down.

Source: Motion Picture Association 2012 Theatrical Statistics

So far in 2013, only one movie, “Iron Man 3,” has grossed more than $400 million domestically. In animation, a perennial box office stalwart, only “Despicable Me 2” surpassed the $300 million milestone, with its take to date at over $350 million. Seven movies, four of which are sequels, collected over $200 million as of Labor Day Weekend. While the year is not over, to date 21 movies have broken through the $100 million ceiling.

Compare this to 2012, where the chart topper, “Marvel’s The Avengers,” registered $623 million in domestic sales followed by two movies, “The Dark Knight Rises” and “Hunger Games” above $400 million, two more, “Skyfall” and “The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey” over $300 million, and another six releases taking in over $200 million. In all, 31 movies in 2012 grossed more than $100 million in domestic box office, one more than the previous year’s total of 30.

Rusty Citron, founder and CEO of Studio Direct, looks beyond the grosses to track the proportion of seats sold and unsold. Not surprisingly, the “utilization” of theaters is low and the percentage of unsold seats is high. For example, the #1 movie of the August 24-25 weekend, “Lee Daniel’s The Butler,” sold only 18 percent of the total seats available. Citron bases his count on the total number of screens in the U.S., 38,000, and an average of 250 seats per theater for a total of 9,500,000 potential seats to fill.

Rusty Citron, founder and CEO of Studio Direct, looks beyond the grosses to track the proportion of seats sold and unsold. Not surprisingly, the “utilization” of theaters is low and the percentage of unsold seats is high. For example, the #1 movie of the August 24-25 weekend, “Lee Daniel’s The Butler,” sold only 18 percent of the total seats available. Citron bases his count on the total number of screens in the U.S., 38,000, and an average of 250 seats per theater for a total of 9,500,000 potential seats to fill.

Unlike other industries where inventory adjustments can be made according to market demand, theaters are fixed in size. Digital Cinema has made it possible to “load balance” theaters by playing movies on screens best suited for the size of the anticipated audience. It has also made it easier to place high demand movies on more screens. But there is little that can be done to fill during the off-peak hours and days. However, some new companies, like deal/discounters Dealflicks, Chimpflix, and screen-on-demanders Tugg and Gathr are providing innovative antidotes to the traditional booking model.

The innovators’ response and the proliferation of available screens address emerging audience behaviors. These are trends shared by television and movies. In fact, the roles are almost reversed now. Television is increasingly where characters and stories have a chance to develop and flourish, while the blockbuster features take fewer chances as they race to capture screen share and revenue in the first two days. The sportification of box-office reporting, where the only thing that matters is being number 1, creates winners and losers in public perception — often before the first weekend is over.

Compound this with two other factors: the number of ways audiences can chose to enjoy movies and the pressures that studios and producers face to attract their initial audience.

Citron notes that in the early 1950s there were about 10,000 screens where people could watch movies in the U.S. There were no twin or multiplex theaters. The biggest movies were “road shows” with hard tickets to reserved seats. Moviegoing itself was an event.

Flash forward to 2013 and the audience now has a choice of well over 250 million screens on which entertainment can be viewed. Yes, million. This figure includes televisions, computers, smartphones and tablets:

- Television Households = 115 million (source: Nielsen)

- Smartphone Ownership = 141 million (source: comScore)

- Tablet Ownership = 34 percent Adult U.S. Population (source: Pew)

- PC Ownership = 76 percent U.S. Households (source: U.S. Census)

- Broadband Connectivity = 70 percent Adult U.S. Population (source: Pew)

The proliferation of screens, both actual movie theater screens and the multitude of alternative viewing opportunities, is reflected in the average weekend-to-weekend box office drop. Charts on Box Office Mojo reveal the trend over the past two and a half decades. In 1987, when “Beverly Hills Cop 2” was the #1 movie of the year, the average drop-off the opening weekend was 26.4 percent. A decade later, the average drop rose to 42 percent and since 2007 has hovered in the vicinity of -50 percent. Audiences no longer wait for the crowd to die down because virtually all of the data suggests that there is no need to wait.

Back in 1987, while “Beverly Hills Cop 2” ruled, that other movie, “Ishtar,” suffered for several contributing reasons, not the least of which was the antithetical portrayals of the two enormous stars, Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman. Their onscreen characters could not have been further apart from what their audiences wanted to see. According to an executive quoted in the previously referenced NY Times story, “If you’re buying those two actors, you’re buying them as movie stars. Audiences don’t want to see Warren having trouble getting women and Dustin covered in sand.”

Traffic jams of movies with similar themes were symptomatic this year but not novel. In 2007, hardly the first occurrence, there was “March of The Penguins,” “Happy Feet” and “Surf’s Up.” Fresh and fun as “Surf’s Up” was, well reviewed and nominated for an Academy Award, it was the third penguin movie of the year and it wiped out.

These traffic jams produce another dilemma at the box office.

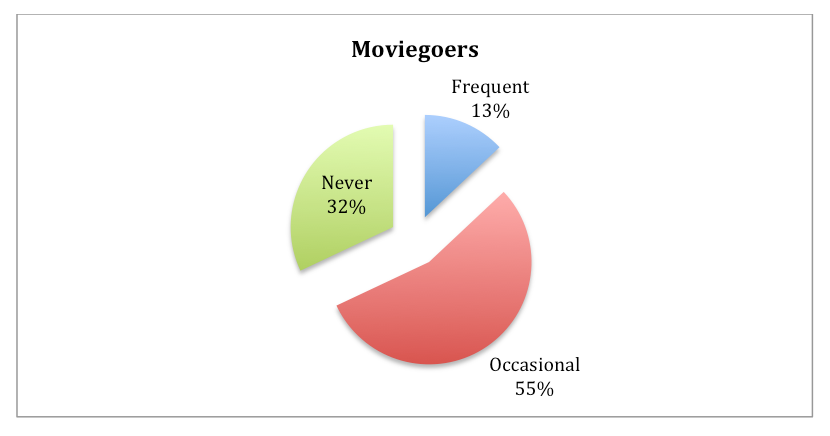

Despite the fact that fully two-thirds of the U.S. population (68 percent) will go to a movie theater at least once a year, according to the Motion Picture Association, the number of people who can be considered “regular” or “frequent” moviegoers, those who attend at least once a month, is relatively small at just 13 percent. This 13 percent account for 57 percent of the total ticket sales. Data suggests that the least frequent moviegoers may be taking in an additional movie.

From an all-time, attendance frequency high of 34 movies per capita per year in 1946, after World War II and before television, the average reached its nadir in 1971 when it declined to just 3.4. The average has hovered between four and five movies per year since then, with the most recent reported year, 2012, showing 4.3 (source: http://www.waynesthisandthat.com/moviedata.html).

Each weekend, movie marketers reach out to the same approximately 41 million frequent moviegoers, that core market of individuals who reliably buy tickets at least once a month. Of course, hits happen when these marketers connect and motivate portions of the remaining 55 percent of the population who will be highly selective about which movie will be the one or two, or maybe three, that they will see this year. But on a weekly basis it is this pie of 41 million people who are in play (sources: U.S. Census Population Clock and MPAA Theatrical Statistics).

Audiences are not just more selective; they seem to be more discerning. They choose more carefully how and on what to spend their limited discretionary dollars and with the myriad of viewing options now available to them; they can afford to spread their entertainment dollars across a variety of platforms and venues without necessarily missing anything they truly want to see. This is one reason why in a summer of multiple apocalypse movies, the audience was in no hurry to spend their money on more than one.

Ann Hornaday, writing recently in The Washington Post, comments, “As we learned last summer, which featured such debacles as ‘John Carter’ and ‘Battleship,’ quality still counts. Studios, which generally avoid movies that are novel or risky or not based on a comic book because they’re ‘execution dependent,’ may slowly be realizing that everything’s execution dependent, no matter the star, source material or special-effects budget.”

The family market is particularly susceptible when the competition between multiple movies appealing to the same demographic crowds the market. Where the typical “core moviegoer” between 18 and 34 is paying for himself or herself or maybe one other, families tend to be one or two adults and two or more children. Add in refreshments and the decision to go to the movies is a substantial spend. Compared to sports, theme parks, concerts and other events, it is still a good value but it is also not something that many families can do on a regular basis.

The early and phenomenal success of the Pixar movies was due in some measure to the fact that they were the only films with appeal to that then underserved market. Not only were their movies original and excellent in their production, but also they had the market to themselves.

Early evidence of a crowded market was seen in 2002 with the release of the sequel to the 1999 hit, “Stuart Little.” The original movie opened on December 17, 1999 at #1. It was #1 at the box office three times in its first four weeks of release, didn’t drop below #3 during its first six weeks and held top 10 positions for 10 consecutive weeks. The movie grossed over $300 million worldwide with about 47 percent of that tally from the U.S. and Canada. There were no other movies for families during a peak family time of the year and “Stuart Little” was a roaring success.

Three years later, in 2002 and based on the strength of the original, Columbia Pictures released “Stuart Little 2,” which many considered an even better movie than the first, on July 19, 2002. By then the audience was exhausted and most likely out of cash. Starting with “Spider-Man,” families had likely already seen “Star Wars: Attack of the Clones,” “Scooby-Doo” or “Lilo & Stitch.”

The starkest example more recently is the comparison between Thanksgiving 2011 and Easter 2012. “Puss in Boots” was released just before Halloween 2011 and enjoyed a successful run and clear market for most of November, when “The Muppets” and “Happy Feet Two” opened. The following weekend, Thanksgiving, introduced the year-end holiday-themed “Arthur Christmas” and “Hugo.” While all of the movies did business, “Arthur Christmas” and “Hugo” opened well below expectations.

A little over three months later, on March 2, 2012, “The Lorax” opened to over $70 million. There had not been a significant new movie for the family audience since “Alvin and The Chipmunks: Chipwrecked” on December 16.

The $70 million total is not just the story of a great opening weekend. Look a little closer and you start to see a more accurate reading of the market. Go back to Thanksgiving weekend. “Puss in Boots” did $7.5 million; “Hugo” $11.3 million; “Arthur Christmas” $12.1 million; “Happy Feet Two” $13.4 million; and “The Muppets” $29.2 million. Add them up: $73.5 million.

The family audience didn’t avoid movie theaters that Thanksgiving weekend. They were there. Except instead of crowding into the same movie, the cohort had a choice and made it.

When the choice is made not to see a movie in the theater, it is not the same as deciding never to see it.

The same screens and alternatives that can be seen as competition can also be salvation.

How different is the availability of a title on Netflix, Amazon or Blu-ray from the time-shifting habit begun with recordable media in the home and especially the introduction of the DVR, which now number more than 50 million? (Source: Nielsen.) In the decades since home recording of entertainment for personal enjoyment at the convenience of the paying customer, the audience is now accustomed to the ability to be entertained by what and when they please, which doesn’t exclude time and place-based options.

How different is the availability of a title on Netflix, Amazon or Blu-ray from the time-shifting habit begun with recordable media in the home and especially the introduction of the DVR, which now number more than 50 million? (Source: Nielsen.) In the decades since home recording of entertainment for personal enjoyment at the convenience of the paying customer, the audience is now accustomed to the ability to be entertained by what and when they please, which doesn’t exclude time and place-based options.

The “Netflix effect” is seen on both television and movies. When Chris Anderson wrote The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More, he credited Netflix with enabling obscure movies to find an audience and breathe economic life simply by making them available. With infinite shelf space to service the exponential growth of viewable screens and content, rushing to the 8 o’clock show doesn’t have the same urgency.

(Check out this excerpt video of Anderson talking about Long Tail Theory — and this video of Anderson’s conversation with Will Hearst at the Long Now Foundation.)

In some ways, this dovetails with the need for efficiency in theaters. Exhibitors depend on maximum traffic; studios concentrate their marketing spends to build to a big opening; and the audience wants plentiful and convenient show times. With average drop off now at 50 percent, it’s down to the opening weekend. One and done, almost.

Except Netflix is proving other models. Binge viewing has given second life to television series and helped multiple shows to actually build their audiences. Where movies have but a weekend to make their mark, programs like “Mad Men” and “Breaking Bad” grow from season to season, deepening their characters and story development as they grow their audience.

Witness the final season debut of “Breaking Bad” in this account from The Hollywood Reporter: “‘Breaking Bad’ surged to a series record Sunday night, bringing in 5.9 million viewers in its first airing — nearly doubling its previous high. The start of the AMC series’ final eight episodes, the jump makes a compelling case for how many viewers have found the series on Netflix, DVD and On Demand during its lengthy hiatus. The first half of the series’ final season opened with 2.9 million viewers last July, making for a 102 percent gain, year over year. A record at the time, the series eclipsed the haul several episodes later with 3 million viewers tuning into the penultimate episode before the show’s break.”

The availability of “Breaking Bad” on Netflix is beneficial to both the network and the streaming service, writes Esther Zuckerman on The Atlantic Wire: “[Zachary Seward of Quartz] noted that AMC is ‘more progressive than nearly any other cable network’ in sharing its shows on the Internet. In fact, the network is allowing UK Netflix users to watch new episodes on the site nearly immediately after they air. Andrew Wallenstein at Variety credited the ratings boost that ‘Breaking Bad’ saw Sunday night to the binge watchers who caught up on the entire show on Netflix.”

Master moviemakers George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, arguably the two filmmakers most closely associated with the establishment of the era of blockbuster movies, addressed the upheaval in the movie industry at the opening of USC’s new School of Cinematic Arts building in June of 2013. While they stoked controversy with predictions of variable ticket pricing and an implosion when a series of massively budgeted movies fail, they also suggested an inevitable paradigm shift that reaches beyond but not to the exclusion of the big screen.

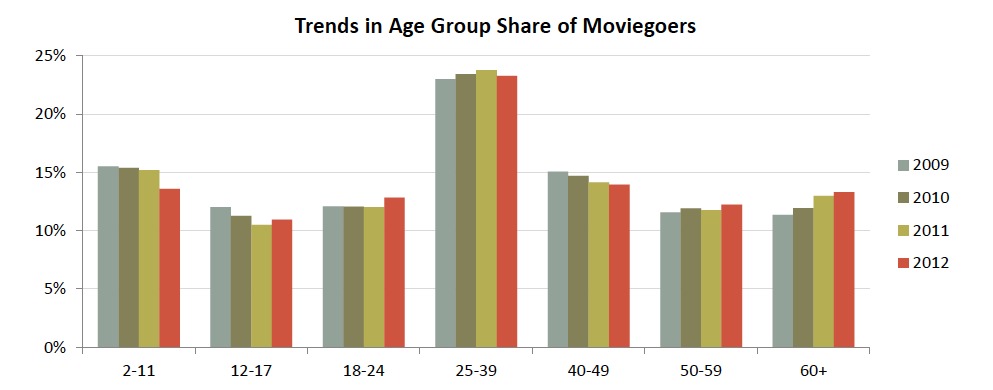

Between the obvious changes, such as the precipitous week-to-week box office drops and incredible activity on television and online video, data from the MPAA can suggest another possible canary in the coalmine of theatrical movies. Over the past four years, the age group trends pick up an indicator worth tracking. Easy to get seduced by the big column of 25-39 year-old moviegoers with just a slight drop, maybe not too alarming, last year, especially with a nice little bump in the 12-17 and 18-24 year-olds. But was that just “The Avengers,” “The Amazing Spider-Man,” “The Dark Knight Rises,” “Skyfall,” “Ted,” “Brave” and the “Twilight” sequel drawing them out?

Look at the 2-11 year-olds and the 12-17s. The youngest segment was flat and then had the sharpest decline of the lot. The 12-17s evidenced a steady decline except for the most recent year. And the 18-24s have been almost pancake flat for three years until a banner year for movies that suited their tastes. Meanwhile, on the upper end of the chart, the oldest audience segments are growing. The caution is that the audience can only age so far before they are physically unable to go to the movies. To be blunt, it is hard to bank long term on a dying audience, especially when the youngest audience segments suggest they are taking advantage of multiple channels of viewing, not to the exclusion of going to theaters, just no longer exclusively.

Source: Motion Picture Association 2012 Theatrical Statistics

Viewed as separate and isolated businesses, legacy businesses and business models are undeniably challenged. However, in aggregate entertainment is in higher demand than ever. More people are enjoying more entertainment in more places than ever before. “Through a decade of economic and technological upheaval, the entertainment industry grew 50 percent while consumers increased spending on entertainment,” writes insight firm Floor64 founder Mike Masnick and research executive director Michael Ho, co-authors of The Sky Is Rising.

The magic of the darkened cloister of a movie theater where an immersive experience of light and sound, story, structure and characters transports people from the ordinary to the extraordinary will endure even if it changes. It is even clearer now that there will also be other places, different places, a variety of places and a myriad of ways and platforms and devices where stories will live and be told. Motion pictures — moving images — these are alive and well. Just as younger generations are more socially tolerant and see fewer differences between people, the same trend may be true about the movies. It matters less to the emerging audience where or how they watch a story unfold. Movies, television, online? How big a difference is there if you think of it all as visual storytelling?

It may be hard to exactly predict the future, but at least one thing is certain… there will always be stories and people interested in them.

No Comments Yet

You can be the first to comment!

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.